Kawase Hasui (alias of Kawase Bunjirō) was born in Shiba,Tōkyō, on18th of May,1883 in a family trading fabrics. Since childhood, he was under the influence of a culturally exciting family background: his mother was the sister of Kanagaki Robun, a Meiji-eve (1868-1912) writer close to the Kabuki theatre environment; it is not coincidence that actors are portrayed in some of his artworks. Kawase Hasui was in poor health, forced as a child to live often with his aunt around the Shiobara hot-spring place, north of Tōkyō. By the way, those scenarios of childhood were crucial for his creative inclination for landscaping.

As already mentioned, the family environment played a decisive role in inspiring Kawase Hasui with the artistic sense. But on the flip side, he was forcibly engaged in the household trading until the age of 26, namely in the occasion of his sister’s marriage because, right after, the above activity turned over to the sister and her husband. Free at last, he approached soon Master Kiyokata Kaburagi, which rejected him for being a bit older, but otherwise recommended apprenticeship to the Okada Saburōsuke workshop. Here, the young artist was educated to use the western art techniques, specifically oil painting and watercolor. Two years later, he was finally accepted on demand by Kiyokata Kaburagi, which taught him how to use the mainstream ukiyo-e and Nihonga genres, and called him Hasui that reads “water flowing from a spring”, while Kawase means “river rapids”.

After visiting the Itō Shinsui exhibition, where he had the chance to see the series of prints entitled Eight Views of Lake Biwa, Kawase came for the first time into contact with the late Shin-hanga genre that impressed him so much that he drove to meet the charismatic figure of Watanabe Shōzaburō, editor and promoter of that artistic movement. This fellow commissioned the artist to implement a trio of test prints, which were realised and exhibited in the 1918’s and ever since then they actively cooperate, until the moment that the author died. The first wood matrixes were lost in the fire after the 1923 Kantō earthquake – also the Watanabe Shōzaburō atelier and the Kawase house were destroyed in the same circumstances – which is why the value of the prints produced before that date fatally increased. That awful event did not stop Kawase Hasui to resume its artistic undertaking, also comprising travels aimed at drawing artistic inspiration. None of his artworks have been realised indoors, all of them being based on sketches done outdoors in real life. He was very able to sketch out landscapes, and then approached somewhere the subject in order to pick up those details he could hardly see remotely because of his reduced visual acuity. Last, he gave specific instructions to the printer as regards colour selection he himself watercolored in advance. The final production was therefore the result of careful workforce interactions involving engraver, printer and editor altogether engaged to make changes, occasionally, with a view to the floating market tastes: Kawase Hasui remarked on that practice by saying that his prints ultimately were best or worst, but scarcely in keeping with the original design in all relevant detail.

Preference is expressed by the author for sceneries substantially departing from the traditional ukiyo-e trend of targeting famous places (meisho-e). Conversely, his artworks are intended to disclose the inner, genuine spirit of Japan by rather reproducing underestimated details of the more remote and rural Japan. In line with this approach, any evocation of modernity was prevented as much as possible by inspiring the observer of his prints with thoughts of the past through a powerful wave of peaceful nostalgia engulfing the scenery. A few human figures are captured, and urban scenes are devoid of crowd, maybe because of his impaired vision of short-dimensioned things, all the more so if they were in movement. It must also be born in mind that he had a fondness for lonely, pretty arcane and relaxing ambience.

Kawase managed to reconcile the traditional subjects of the Japanese art with the techniques that are typical of the west Realism, notably prospective and chiaroscuro. He was also successful in combining the typically Japanese atmosphere sensitivity with the study of light: this is the case for the changing weather conditions and different moments of the day, a pair of situations he found pure evocations of moods. In this connection, he skilfully captured nightly, rainy, misty and snowy scenes, as appropriate.

Kawase never became rich for a variety of reasons because he was taking money in relation to the number of prints he was selling, but always cheaply and, on the other hand, the necessary travels and visits had proved costly. In addition, he saw his home broken up twice: during the Kantō earthquake and, later, during the firebomb raids on Tōkyō. Our author was set in tradition to the extent practicable: he refused to wear western clothes, methodically replaced with the kimono, and used to drink sake; he was rather righteous, careful and efficient, but that did not stop him from being playful and maintaining a sense of humour. It is not accident that he used to call himself with the ambiguous nickname “hanga-do”, approximately meaning “author of prints”, but also “semi-serious artist”.

In 40 years of activity, Kawase produced more than 600 prints, mostly Japanese scenery during the Taishō eve (1912-1926) and the early 1912-1926’s corresponding to the Shōwa eve. In 1956 the artist was awarded the prestigious title “National Living Heritage of Japan”. He worked relentlessly until his death on November 7th, 1957: his last artwork, entitled Hiraizumi hall of the golden hue, was exhibited posthumously and distributed, as part of a celebration in memory of the author, by Watanabe Shōzaburō. The American collectionist Robert O. Muller was the one who popularised the Kawase prints in the Western world.

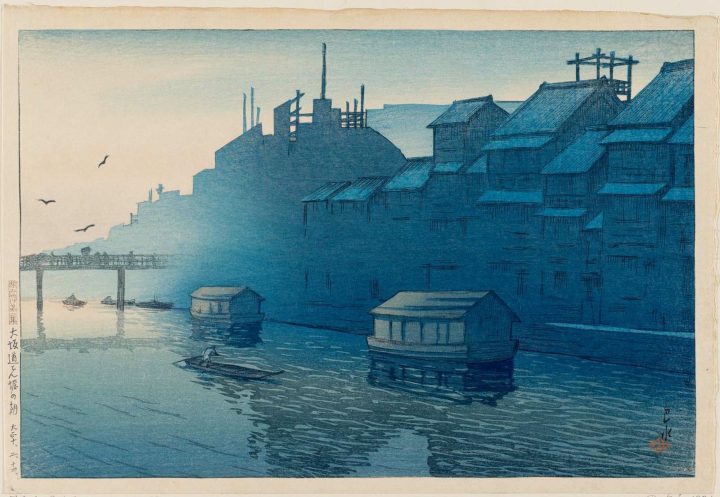

Morning at Dōtonbori, Ōsaka, from the Series Souvenirs of Travel II, 1921, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Morning twilight comes from the left-hand side of the image, and in doing so dissipates the latest bluish shadows of the night. The light effect is enhanced by the basic pigmentation all its own. The prospective is rather a matter of atmosphere – as it is the case for the Chinese ink painting – than geometry: the clear vision of the array of houses becomes quickly diminutive over distance, and ultimately fades in the shiny dust. The foreshortened view of the river suggests that the vessels are convected, in a fluid-dynamic sense, towards the horizon. It is almost like the seagulls are swimming in a river of light adjacent to the real river.

Evening Glow at Yanaka, from the Series Twelve Months in Tōkyō, 1921

Evening Glow at Yanaka, from the Series Twelve Months in Tōkyō, 1921

Against the previous morning twilight, gladly providing hope, a sort of quiet melancholy may be perceptible in the autumn evening depicted here. A majestic Buddhist temple stands in between the barren tree in the foreground and the forest in the misty backdrop. The scenario is construed to arouse an upwardly directed tension. The tree nakedness dramatically evokes the decline of nature at this time of year, while the fly of a lonely bird conveys a sense of stark gravitas.

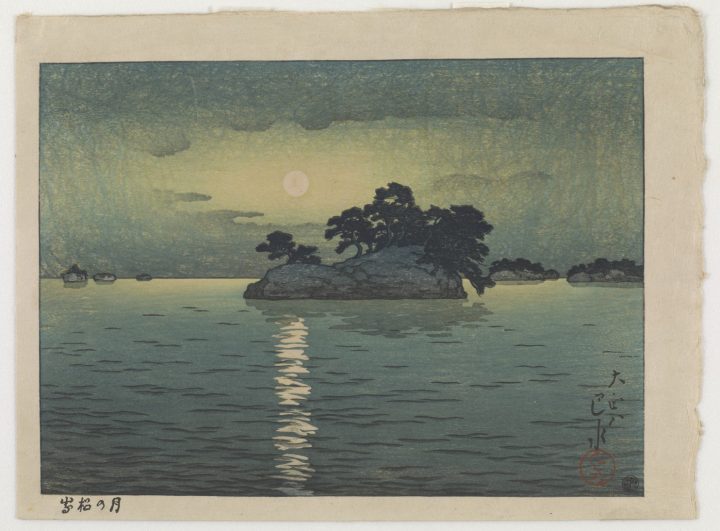

Matsushima in the Moonlight, 1919

Matsushima in the Moonlight, 1919

Matsushima, an archipelago of 260 islets covered by pines, is one of the three panoramic views of Japan. A solitary isle is a typical subject reflecting the spirit of Kawase Hasui who, do not forget, suffered a lot from aloneness in his lifetime. Behind the backdrop, the moonlight emerges in silhouette from the broken bank of clouds and turns into liquid in the sea.

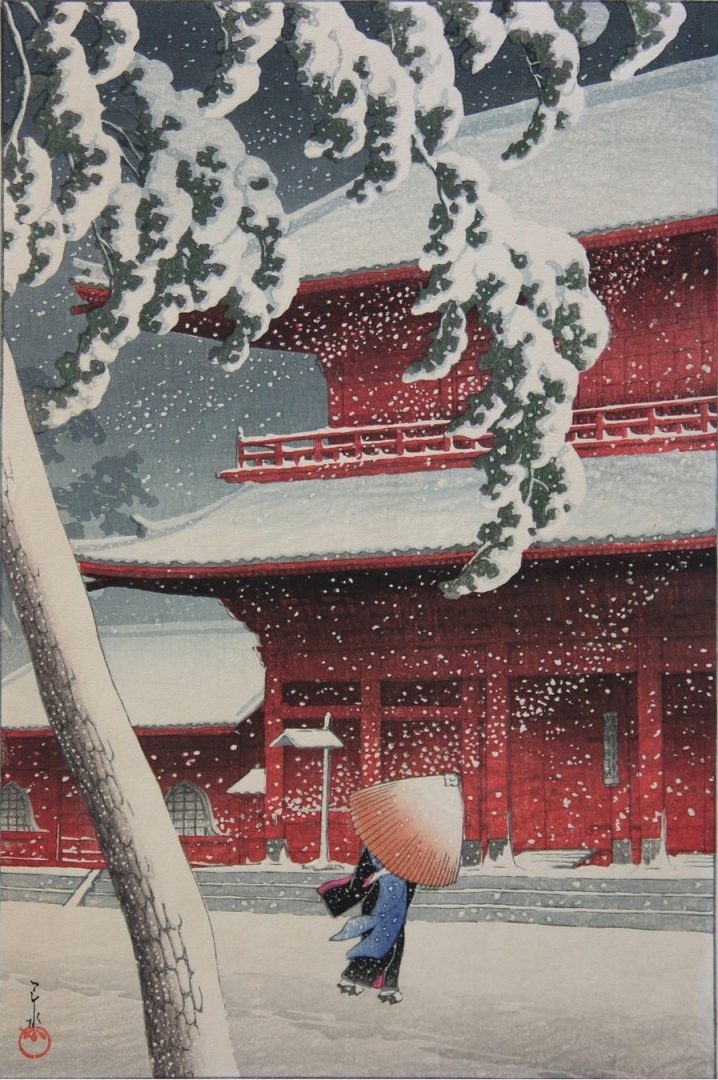

Shiba Zōjō-ji, from the Series Twenty Views of Tōkyō, 1925

Shiba Zōjō-ji, from the Series Twenty Views of Tōkyō, 1925

Behind a tree that is not entirely in the visual field (according to an artistic mode of representation typically adopted in Japan, so that the observer is asked to integrate reality with imagination), a snowstorm is represented. The white flakes contrast strikingly with the red temple, and a certain sense of sacredness cannot fail to be felt. The most revealing part of the walking woman is hidden behind the umbrella, as if to communicate a sense of mystery. Bear in mind that Kawase Hasui infrequently portraits humans and, when he does, he avoids the visual contact between them and the spectator, so expressing the human condition infused with solitude and secrecy. Woman, temple, snow: the suggestion bred into the viewer by that right combination of components has ensured that the print was rewarded with the title of “National Heritage of Japan”.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved