The ukiyo-e developed throughout the Edo eve (1615-1868), thus until the transition to the Meiji eve (1868-1912) that marked the openness towards the West. In fact, new competing techniques, notably lithography and, later, photography signaled the decline of the ukiyo-e since it found its raison d’être in the production of picture books and kabuki theatre’s, food service’s and press’ orders of essentially advertising nature. For survival, it was mandatory that the traditional woodblock print was ready to innovate as for the style and look, in the meanwhile, to the western markets.

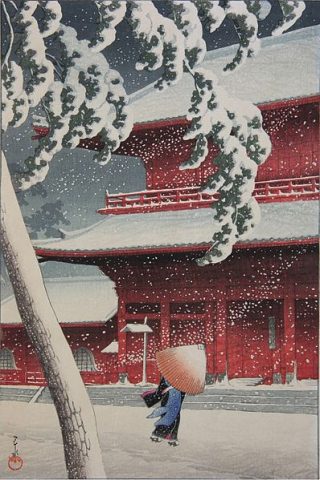

Kawase Hasui, Shiba Zôjôji, from the Series Twenty views of Tokyo

Exactly this was the remarkable insight of a true leader whose name was Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885–1962) that promoted in the Taishō (1912-1926) and Shōwa (1926-1989) periods (hence, before the beginning of the World War I until the dead of Shōzaburō himself) the Shin-hanga (“New Print” Movement) onset. Shōzaburō was an editor that gathered about him a group of poverty-stricken artists and relaunched the typically Japanese art of the woodblock print with the collaboration of the traditional hanmoto (ukiyo-e workshop) “quartet”, individually made up of editor, artist, engraver and printer. Differently from the ukiyo-e prints, that passed for only being, according to the Japanese audience, a low valued mass-marked craft-trade product, the Shin-hanga prints were aiming to achieve the quality equal to the genuine artistic products.

On one hand, the “New prints” were in line with, but on the other revised, the traditional ukiyo-e. This in the sense that the canonic subjects held steady, namely the fukeiga (landscapes), meisho-e (famous views), bijinga (female figures), yakusha-e (actors) and kachōga (plants and animals), but the adopted style was innovative by virtue of the evident influence of the western taste for Impressionism and Realism.

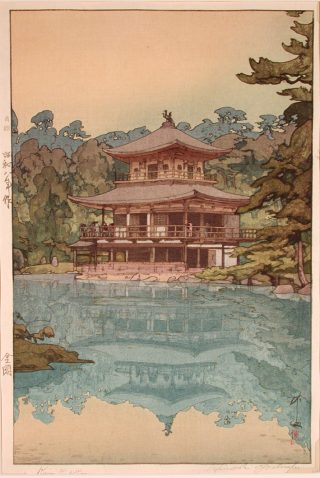

The Shin-hanga artists substantially replaced black outlines, typically adopted in the ukiyo-e, with wide ranges of nuance, especially those resulting in tenuous and subtle gradients. They extensively used the chiaroscuro, deep space, 3D rendering and reproduction of naturalistic light. As an example, Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950) has been known for realizing typically impressionistic experimental prints, since a given subject is represented in a sequence of times of day with the purpose of exhaustively investigate the daylight effect. Last, in the representation of the human subject, the Shin-hanga authors placed particular emphasis on feelings and character.

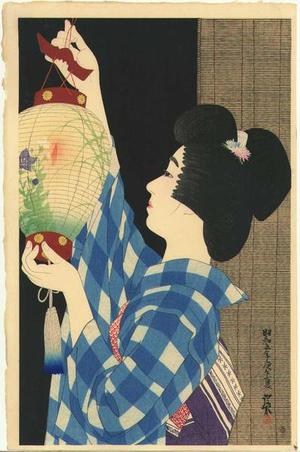

Shinsui Ito, First Series of Modern Beauties, Paper Lantern

In response to the vibrancy permeating the ukiyo-e and to a rapidly-dissolving world, a rather nostalgic feeling runs through the Shin-hanga prints. That world is made of wooden buildings, fishing boats and geisha wearing traditional clothing; that world is the countryside Japan. The landscapes, such as those of Kawase Hasui (1883-1957), which make up most of the production of this movement, look as they are under the inevitable threat of a future, or are about to be wiped out forever by an on-going, urbanization. Therefore, the artwork category under examination does reflect a romantic and melancholic vision of Japan, with very suggestive effects on the western observers.

The most prominent artists of Watanabe Shōzaburō’s group were Kawase Hasui (landscapes), Ohara Koson (1877-1945, plants and animals), Natori Shunsen (1886-1960, theatre actors) and Itō Shinsui (1898-1972, bijinga).

Ohara Koson, Kingfisher and Irises

Even though Watanabe Shōzaburō was the promoter and the undisputed point person for the Shin-hanga, his movement accommodated artists from outside the atelier, as it was the case for Hiroshi Yoshida and Goyo Hashiguchi (1880-1921).

Hiroshi Yoshida, The Golden Pavilion

A captive audience for the Shin-hanga was contributed by some western artists, which lived for a while in Japan and authored a number of prints according to the Shin-hanga style. Fritz Capelari (1884-1950), an early collaborator of Watanabe Shōzaburō, was one of them.

The 1923 big earthquake was the cause of a transitional setback: a consequent raging fire resulted in the destruction of Shōzaburō’s atelier along with all the wooden plates for printing. This is the reason why the Shin-hanga prints from before that serious event are higher-valued by the art-collectors. Later, the movement gained rapidly and its international success held traction, a situation held until the 30’s. In that period, the exhibitions at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio in 1930 and 1936 were the most prominent events. Instead, the “New Prints” did not do so much for public affirmation stateside, exactly because they were there considered, as has already been mentioned, a mere replication of the outdated and always unappreciated ukiyo-e. No room there was, say, for the prints of the new movement in the Bunten art exhibition, of which the Japanese Education Ministry was the organizer.

The decline became more severe in wartime because of the military regime’s control on fine arts and culture. As if that was not enough, the invasion of China and, more importantly, the attack on Pearl Arbour in 1941 were key factors for the commissioning breakdown. The movement resumed somehow its activity after World War II and then definitively broke up, owing to both the advanced age of its representatives and death, that took place in 1962, of Watanabe Shōzaburō. Notwithstanding this, some prominent artists like Toshi Yoshida (1911-1995) successfully went on producing Shin-hanga prints.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved