In the 17th century, in the wake of centuries of warfare, the clan of the Tokugawa shoguns was successful in establishing in Japan a long period of peace. In 250 years of centralization of power, that dynasty brought about overcoming of previous feudalistic ways and transition to a commodity economy protected by an autarchic regime (the policy of isolation from the West). As a result, the towns and the middle class provided fertile ground for the artworks to be commissioned and even inspired. This was the Edo eve (1603-1868), so called because the shoguns decided that Edo, the modern Tōkyō, had to become the capital of Japan.

In the 17th century, in the wake of centuries of warfare, the clan of the Tokugawa shoguns was successful in establishing in Japan a long period of peace. In 250 years of centralization of power, that dynasty brought about overcoming of previous feudalistic ways and transition to a commodity economy protected by an autarchic regime (the policy of isolation from the West). As a result, the towns and the middle class provided fertile ground for the artworks to be commissioned and even inspired. This was the Edo eve (1603-1868), so called because the shoguns decided that Edo, the modern Tōkyō, had to become the capital of Japan.

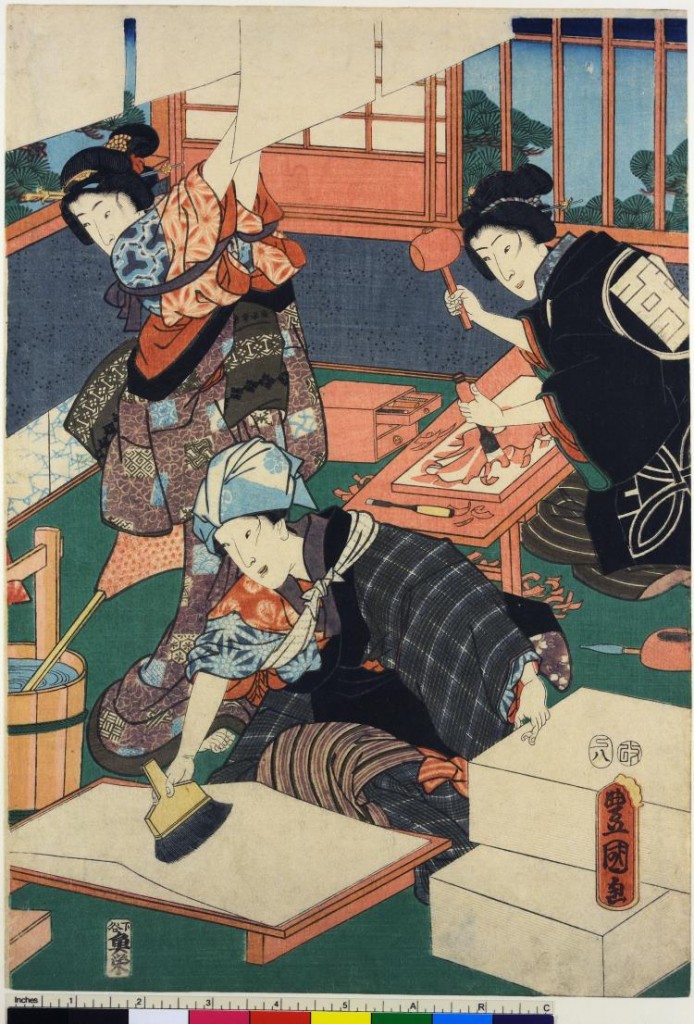

The period under examination nourished the ukiyo-e, namely that artistic movement producing woodblock prints. They enthralled the Impressionists so much that the West is prone to identify the Japanese art precisely with that special works. The printing technique turned out to be a sort of artwork democratization: a large amount of replicas could be made and “stocked” by a single plate, and this allowed the cost of the prints actually put into circulation to be remarkably reduced against high production costs.

The reproduced subjects, which were selected from those actually capable to enrapture the city dwellers, sought inspiration from moments of the social life in the cities, notably from celebrations, entertainment, performances, pretty women dressed modern and smartly. The name ukiyo-e given to that movement already embodies the spirit of a time when people tempted to relieve distress and anguish of everyday life by worldly pleasures, thus forgetting the Buddhist education. According to this education, all those pleasures fall into a “floating world” (ukiyo), namely into a so transient, fleeting world that it is not right to enter into, and, indeed, it is preferable to steer clear from that.

The printing process was very complex and involved a number of different professionals. To begin with, the artist, commissioned by an editor which was funding the whole project, implemented the ink draft and got an idea of the full coloring. The tentative drawing and coloring was thereby subjected to censorship and possible approval granted by affixing an official round stamp. By the way, consider that a censuring law was adopted in 1842, after a print with 72 color shades was published, that restricted sharply to only 8 the maximum number of permitted shades. Indeed, meeting this moderating condition for coloring in fact resulted in a successful result, as it is the case for Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

The drawing was at a later stage handed over to the engraver (horishi) which arranged it facedown on a suitably aged and processed wild hardwood cherry board. The special wood grain occasionally appeared on the prints, thus giving them an additional decorative. The paper surrounding the outlines was scratched out, the lines were debossed on the molding side and the unoccupied outer gaps were removed with a chisel. As soon as the original drawing was destroyed, the outer edge of the woody plate was registered by a tick, so the pressman could get the sheet to be printed in the right position. India-ink prints were reproduced in as many copies as there were the artwork colors. Later, the printed proofs were set up on as many woodblocks, the processing side of which was abraded in the colored areas likewise the contour engraving. Briefly, one plate for every color.

In the following step of the processing, the pressman (surishi) got to cut a handmade blotting paper, surprisingly derived from the mulberry, produced in the form of strong sheet. He performed the edges by scrubbing the woodblock with an India-ink-soaked brush and then positioned the sheet taking care to respect the indicative tick mentioned above. The pressman used a suitably flat disc to adhere the sheet to the block for the drawing to be pressed. And then, he laid the sheet on the previously prepared blocks for the colors to be impressed, in order from lightest to darkest hue.

Except for the Prussian blue, which derived from a chemical process developed in Europe and introduced by the Dutch into Japan in 1820, the adopted pigments were all of vegetable and mineral origin.

Visual effects similar to painting were provided through the bokashi, namely color shades with 3D rendering. But there was also a sophisticated decorative technique, especially suitable for backdrops, making use of powdered mica (kira-e).

In some cases, even the engraver’s or printer’s name showed up on the artwork alongside both author’s signature and cartouche reporting series and press titles. The latter appeared on the top right, and often resulted in a genuine masterwork in itself because it took up the print colors, or bore refined, short dimensioned drawings, such as clouds and snowflakes.

As regards the ukiyo-e genres, consider that they were connected to several subjects, notably beautiful ladies (the portraits of which were termed bijinga), kabuki actors (the so-called yakusha-e), sexual scenarios (shunga), flowers and birds (kachōga), fantasy topics (kaidan), landscapes (fukeiga) and especially famous views (meisho-e). In 1840, The Tenpō Reforms make the courtesan’s and kabuki actor’s portraits illegal and, therefore, forced withdrawal into historical and mythological scenes.

As regards the genres on the whole, it is worth noticing that the ukiyo-e current proved a renewed interest for man and his figurative depiction. Even though the involved subjects revolved mainly around geishas or kabuki actors, this trend was appreciable because, through the related physiognomy and character studies, prepared the ground for what is known as portraiture. This has previously been taken into account looking at Utamaro and Sharaku. It is only with Hokusai e Hiroshige that the attention shifted away from the human figure to landscape and countryside, a transfer regarded as a renewed interest for something sacred, and therefore more important than human being. Hence, there is a bipolar oscillation in the ukiyo-e between the depictions of man and nature.

The art critic Okakura Kakuzō felt in the aesthetic principle of preventing repetitions, as well as in an ecocentric philosophy, the source of overcoming the human representation in the Japanese art, saying: “Thus, landscapes, birds, and flowers became the favorite subjects for depiction rather than the human figure, the latter being present in the person of the beholder himself. We are often too much in evidence as it is, and in spite of our vanity even self-regard is apt to become monotonous.” (Okakura Kakuzō, The book of tea, Ch. IV, Putnam’s, New York, 1906).

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved

The picture is from: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?partid=1&assetid=694762001&objectid=786108