Ogata Gekkō, Full Moon and Autumn Flowers by the Stream, c. 1895

The moon is a leading player in the Japanese imagination. In Buddhism, the moon has come to symbolize enlightenment, the latter represented not without reason with a ring evoking the former. And it’s just a Buddhist legend that explains how a rabbit-like image was impressed on the visible face of the moon. In fact, an observer positioned somewhere in the Asian countries feels like he is seeing therein a rabbit in the act of pounding something in a mortar. Legend says that during Uposatha, which for Buddhists is a sacred daytime to be devoted to charity and meditation, a monk, an otter, a jackal and a rabbit met a hunger-weary elderly wayfarer. With the intent to be diligent in doing a good deed, they had a contest to see who was able in retrieval of food for that oldman. Accordingly, the monk climbed trees and brought him fruit; the otter jumped in the river and caught a fish; the jackal stole food from houses. Instead, all the rabbit can do was bring grass. He was very disappointed that he was not able to do more and he threw into the fire for his own flesh to be offered to the wayfarer. This, who in reality was a deity, was so impressed with that heroic sacrifice that he drew the image of the rabbit on the moon face as a memory for everyone. The lunar rabbit is a recurring symbol in several Asian cultures, so that, by looking at China, the rabbit has the task of pounding herbs of immortality in his mortar on behalf of the lunar deity named Chang’e.

In the framework of Shintoism, the moon-related deity is Tsukuyomi, the name of which could derive from combining the noun tsuki (moon or month) and the verb yomu (to read or to count). According to an optional interpretation, that name is given by joining the noun Tsukiyo that reads “moonlit night” and the verb miru (to look at). Tsukuyomi is indeed a deity intimately connected to light: according to legend, in fact, he was born from an eye of Izanagi the god, or from one mirror of him.

The Fall holyday called Tsukimi (contemplation of Autumn Moon) is a harvest propitiatory, thus typically rural, holiday during which the moon is pleased with full-moon shaped rice candies and rice-like grass. On Tsukimi day, during the Heian eve (794-1185), the members of the Court used to look at the moon as a source of musical and poetical inspiration. It is not accident, according to the Japanese, that the fresh and clear air in the autumn offers more favorable conditions to be enchanted by the moon.

Utagawa Hiroshige, The Moon over a Waterfall (Hakoshi no tsuki), from the Series ‘Twenty-eight Views of the Moon’ (Tsuki nijūhakkei no uchi), c.1832, Honolulu Museum of Art

When faced with Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e reported above, the question one might ask to himself is how it is that a print like that, produced indeed by an outdated wooden-plate marking technology, so masterfully renders moonlit. The rounded shiny surface contrasted with the opaque background, where blue progressively turns into grey with a sort of bokashi effect. This is about colorful shades for 3D rendering, here adopted for autumn sky to look as deep as it can. Everything captures moonlit: the rushing water, reminiscent of the flow of time, from the fall and the detached red maple leaves floating out there, as if they are evoking the Buddhist impermanence. On one hand, the picture is pervaded by a palpable sense of mystical contemplation and almost, on the other, of bitter reaction to the reminder that time passes and nothing lasts. Such feelings are written on the edge of the print in a poetry form that reads: It is not unbearable to see maple leaves fall / Scattering on the mass-covered ground / It is unbearable to feel the wind grow chilly / And see the whole sky darkening (Trans. by Yoko Woodson).

Utagawa Hiroshige, Rabbits in Moonlight, 1847-52, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Hiroshige also authored the print entitled “ Rabbits in Moonlight”. The moon is only partially enclosed in the picture, so that the observer is tacitly invited to complete the figure with imagination. The rabbits remind of the lunar rabbit that the Buddhist legend tells. The Pampas grass is a species, growing up in Autumn/Winter in that land, which is often reported in the Man’yoshu, the first poetry collection in Japan. Accordingly, the soil is snowy, the snow standing for vacuum in line with Zen. Hiroshige – do not forget – is the master of rain and snow. In the print under examination, the robin’s egg blue sky is the only color whose fineness is increased by the graceful outline adopted.

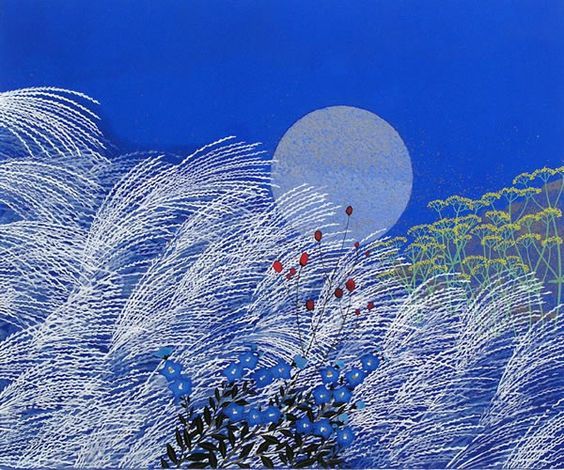

Reiji Hiramatsu

The Autumn grass in Reiji Hiramatsu’s print (see above) reflects the pallor of the moonface against a vivid blue background. Clearly, this is a further example in which graphic design and chromatic essentiality combine successfully.

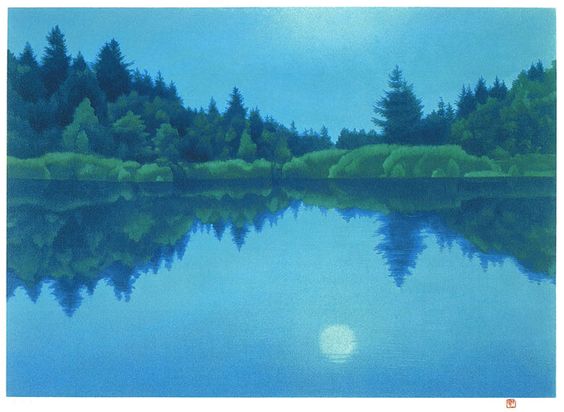

Kaii Higashiyama, Moon Reflection

The shores of a lake were a setting for the artwork by the Nihonga painter Kaii Higashiyama entitled Moon Reflection. Here, the shades of sparkling blue and green make the moonlight effect almost vivid. Instead of being portrayed, the moon is evoked because of its reflection: the absence of that lighty source exercises a suggestion pretty well thought out. According to Shintoism, a single thing is a mirror for all the others, so that the mirroring lake is the moon and the moon is the lake of light.

The poetics of the last two works is entirely founded upon the peculiar Nihonga technique, in turn inspired by the Rinpa art. That poetry is put into practice by creating chiaroscuro-like depth effects through the use of suitably fragmented pigments with varying particle size, thus in alternative to the elsewhere widely adopted color dilution. The dream-like glow settled over Nihonga paintings, with their gentle shades of color, ethereal beauty, interspersed low or vivid light, owe a great deal to the use of pigments according to the centuries-old Japanese tradition.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved