The Japanese sensitivity to nature and beauty of seasons often elicited the artists to represent typically seasonal phenomena, notably those categorized in an atmospheric sense as rain, snow and wind. A recurring issue is precisely snow, thus substantially in contrast with the West art, until at least Monet’s activity. This artist, and all the Impressionists as followers, introduced and then frequently depicted snow under the influence of the Japanese prints.

Indeed, the subject at hand finds its source in the Chinese prototypes, even though typically Japanese landscapes were largely suggestive to artists. Consider that abundant are the winter snowfalls in Japan owing to its central mountain ranges behaving as a barrier against influx of cold air mass, through the Sea of Japan, from Siberia. In fact, the northern edge of that very cold area is known as Yukiguni, which reads “Land of Snow”.

As regards woodblock prints, the clever method to exploit the washi print paper itself, to render snow as a substitute of usual white inks, was largely adopted. This was the case when the subject rather involved large carpets made of snow; the snowflakes are instead created by engraving in the inked woodblock small notches so that, once the woodblock is imprinted on the paper, the latter remains white in correspondence with the notches. But less often, this is the case for de luxe or on order copies, snowflakes were superimposed by spotting white ink (gofun) previously derived from crushed seashells. The final aim was to ensure highlighting effect even on the white paper background. In addition, the pigment was applied randomly, making each print unique, unless stencils with holes were used according to the stencil technique, so that the position and distribution of the flakes were the same in all prints. A further method of snow reproduction was to impress the thick, mulberry derived washi paper by a carved – hence, not inked – woodblock for backlit dashes in relief to give nice three-dimensional rendering.

As a symbol of purity, snow exerts a particular attraction on the Japanese sensitivity: snow is once taken as representative of naïve innocence behind heroic undertakings and also as a subject of prints and paintings in special combination with cherry blossoms. Parenthetically, snowflakes and sakura petals – the latter being a symbol of what is ephemeral and transitional as is life of the hero – get confused in delicate and poetically poignant swirls. Washi paper is also cut into little strips (gohei) hanging as white as snow from ropes (shimenawa) contouring the sacred Shinto sites. In addition, snow is often associated in the haiku (Japanese form of short poetry) to the Zen notion of emptiness. This is because, after the poet Naitō Jōsō (1662-1704), snow covers and clears everything: Fields and mountains / all taken by snow / nothing remains (Jōsō, trans. Horioka, amended by Marsh).

Utagawa Hiroshige, Lingering Snow on Mount Hira

Hiroshige’s artwork entitled Lingering Snow on Mount Hira is included in the Series Eight Views of Ōmi Province which draws inspiration from the Chinese counterpart entitled Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers. The picture couples view to mood, time of day, poetry, and reduces the figure to a pure geometrical form – see the mount ridgelines – somehow evoking one of Paul Cézanne’s subjects. Soaring peaks with fresh snow seem to conflict with the miniaturized downstream villages consisting of cottages with sloped roofs. Majesty of nature and man-made settlements are in harmony, and everything is enhanced. The magnitude of the mounts is not detrimental for describing some dispersed details: see the boat guy who is moving an oar or the old man with a walking stick. The white of the snow is reflected in the twilight, and a sense of blissful quiet, mixed with melancholy fineness, shines through. The scroll verses, on the topic of snowfall in the twilight, are those of Konoe Nobutada (1565-1614) and read: “After snowfall/ the peaks of Hira at dusk/ surpass the beauty of cherry blossoms”.

Utagawa Hiroshige, The Gion Shrine in Snow

Also authored by Hiroshige is The Gion Shrine in Snow (from the series Famous Views of Kyōto), an artwork set now in the city. Here, four geishas are outside the front door (torii) of the Kanshin-in Temple, Gion District, Kyōto. They are wearing thick sandals, made of wood (geta), underneath snake eye umbrellas (janome), and lifting up soberly colored kimonos so that they do not get wet. The author does not fail to highlight graceful footprints disseminated all round. Gion, frequently visited by travellers and templegoers, became one of the biggest districts of pleasure and geisha quarters in Japan. The print observer is captivated by the essential elegance of the choice of colours, which spread from the dancing white snowflakes to the grey sky and snow covered trees, from the light blue temple gate to the deep blue kimonos. The overall picture is far from being a flat and frontal one, but the torii, positioned at a slant, splits it into two parts making the scene rather dynamic.

Ogata Gekkō, Contemplating the snow from inside

Ogata Gekkō’s print entitled Contemplating the Snow from Inside, from the Series Manners and Customs of Women, carries the observer into an intimate domestic environment where a pair of women, one standing up and the other one sat, are looking at the snowy scenery while they converse with each other. The standing one indicates something outwards, the other one warms herself by being close to a brazier because the open window unpleasingly lets cold air in. The vivid pink and purple kimonos and the shimmer of silk are realistically rendered by means of synthetic colours, already in use during the Meiji eve (1868-1912). The bright colours of the interior are in sharp contrast with the monochrome white-grey exterior, almost like giving an idea of warmth against the unfriendly frozen scenery outside the window. The bent branch of bamboo under the weight of snow is, on one hand, a typically auspicious winter symbol, on the other assumes a metaphoric meaning as clearly illustrated by Kaga no Chiyo (1701-55) in verse: One must bend / in the floating world – / snow on the bamboo.

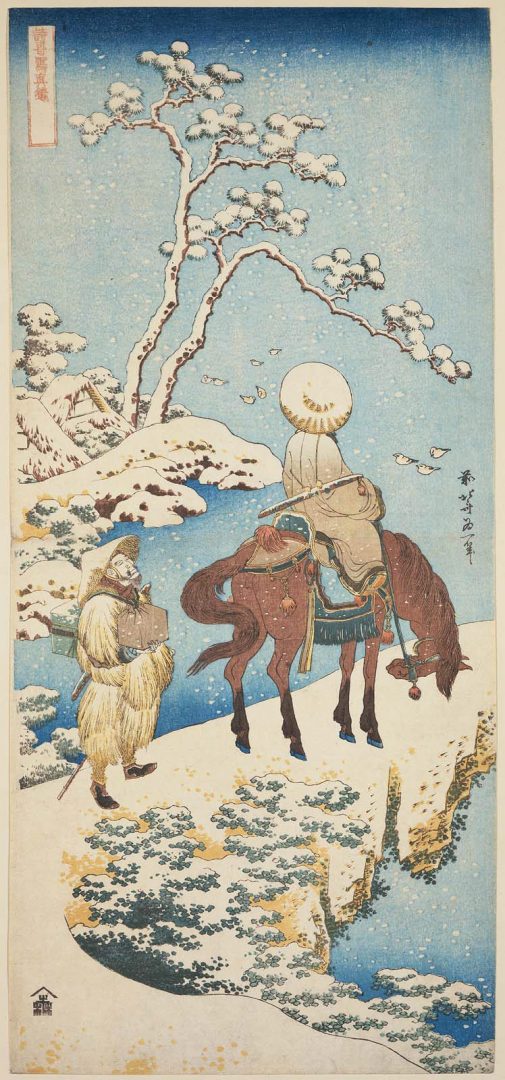

Katsushika Hokusai, Horseman in Snow

According to Hokusai’s artwork Horseman in Snow (from the series entitled True mirror of Chinese and Japanese Poems), the snow-covered background is a lake dotted with waterfowls while snowflakes are falling all around. The observer portrayed from behind, who takes a contemplative stance, is traditionally identified with the poet and Song dynasty’s statesman Sū Shì, (1037-1101), whose Chinese name was changed to Tōba in Japan. The series A True Mirror of Chinese and Japanese Poetry portrays famous Chinese and Japanese poets while immersed in various scenarios. This is the case, in particular, for Sū Shì, who, before being exiled to the Hainan Island, held important government posts and became popular when he built a studio called Snow Hall, which he lined with snow paintings. He was also appreciated for his poems celebrating snow. The horse and the rider seem as being suspended above steep rocks, leading the way to exile, maybe. It is almost as if lake and sky are willing to merge, even though the slanted tree branch bearing the load of snow makes an ideal separation between them.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved