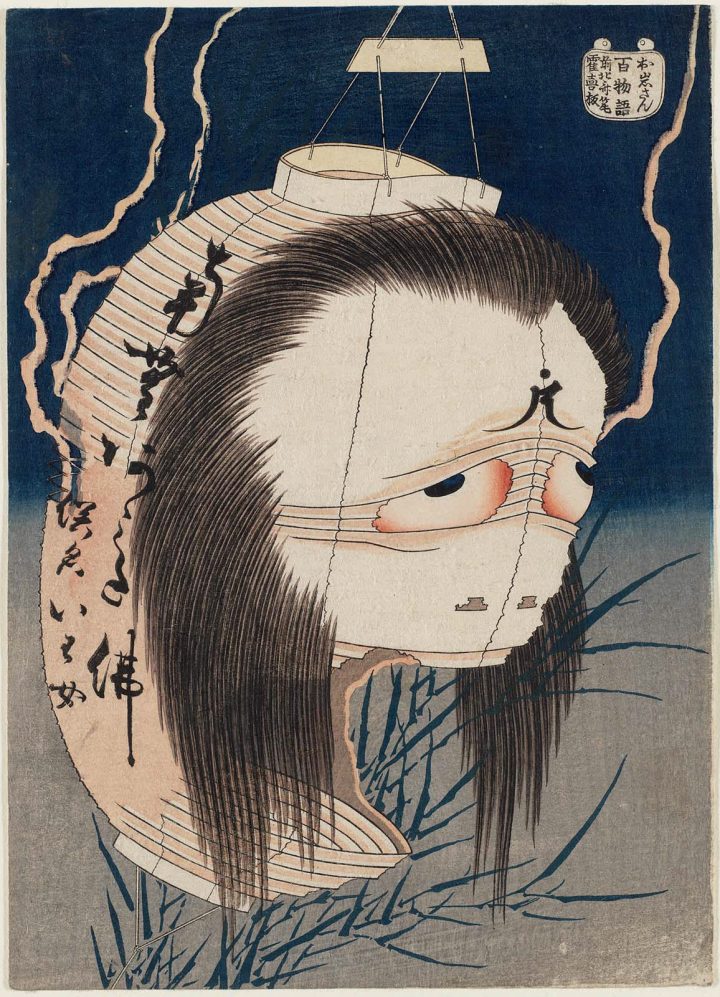

The Ghost of Oiwa (Oiwa-san) by Katsushika Hokusai, about 1831-32 (Edo period), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In general, there is a sort of popular imaginary, alongside the areas of religion and philosophy, that taps into ancient myths and traditions with a connection to magic, fantasy, sensation, fear. All things considered, this is also the case in the Japanese world. I was curious, for instance, about the Japanese people’s believing in ghosts (yūrei) which are envisioned, likewise the western representation, as fading, floating, whitish entities with ill-defined or unstable shape. They are somewhat similar to puffs of smoke coming through unpredictable sites or to floating ectoplasms with long hair, the latter feature being distinctive of the Japanese tradition according to which hair grows even in death.

The ghosts are sometimes figured as spirits that are hiding inside everyday objects which, as a consequence, come to life by posing as terrifying and monstrous mask. As regards, say, an Halloween artistic thinking, I was impressed by the similarity between a jack-o’-lantern, which is of Anglo-American origin, with Hokusai’s animated lantern at hand, a print of the fanciful genre (kaidan) which forms part of the series entitled One-hundred ghost stories (Hyaku monogatari).

Hokusai’s taste for phantasmagoria is already clear from his representation of nature. This has previously been the case for The Great Wave off Kanagawa because of the claw-shaped wave fringing, or for the Waterfalls because of the troubled drafting making them as living entities. The religious idea of a divine presence in things gives way to a purely fantastic imagery where inanimate objects turn into living beings individually possessing a sort of soul and, in turn, determination and temper. It is but a short step from this to the invention of comics and cartoons. The Japanese interpretation of these pastime genres has become increasingly popular, and, as is evident nowadays, not just in Japan.

As an example, the distinctive feature of the cartoon is anthropomorphism, for which typically human personality traits, thoughts and emotions are also assigned to things and animals. That’s exactly what we can see in the Hokusai’s lantern for being gifted with spirit, eyes and mouth. It can be agreed that the caricatural representation aimed at emphasizing expressions of joy, amazement or fear is also typical of the cartoons. Well, even this feature is recognizable in the wild-eyed and freakishly slack-jawed lantern mentioned above.

Even though Hokusai is often regarded as an initiator of the Japanese comic strips also because of his manga (sketchs), this genre indeed draws some primal properties directly from the Japanese art in general and from the ukiyo-e movement in particular. In fact, the cartoon is based on stylization, namely on the synthesized rendering of face and figures by using a small number of seemingly hasty drawings, such as straight and arc-like strokes to represent nose and eyebrows, respectively. Several examples of this sort are exactly typical of the Edo period. In the light of the above, drawing is the key element, as for the cartoon, of the Japanese art, specifically of the ukiyo-e printings since they are prone to an overall linearism achieved through the basic technique of outlining. And finally, the cartoon largely takes account of that magic, fantastic, astonishing, fearsome world which, as already seen, is present also in the Japanese cultural tradition and is revealing about something surprisingly similar to our own imagination.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved

The cover picture is from http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/the-ghost-of-oiwa-oiwa-san-from-the-series-one-hundred-ghost-stories-hyaku-monogatari-129277

The end picture, depicting a yūrei from a Hokusai’s ukiyo-e, is from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y%C5%ABrei