A further movement that stands as counterpart of the Shin-hanga was termed Sōsaku-hanga (“creative prints”). The contrast between Shin-hanga and Sōsaku-hanga, as well as that involving Nihonga and Yōga, goes back to the tension internal to the Japanese artistic overview in the wake of westernization.

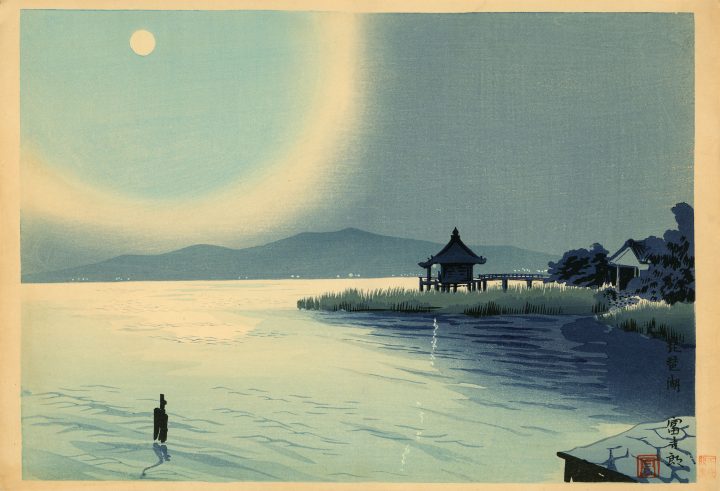

Tomikichiro Tokurichi, Ohmi Katata Ukimido Temple

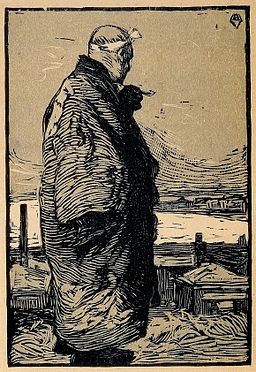

The Sōsaku-hanga genesis stems not from an editor, but from artist teams’ endogenous trends: there is a general consensus in attributing to the print entitled Fisherman, authored by Kanae Yamamoto (1882–1946) and published on The Morning Star in 1904, the character of paradigm for this cultural current. Its key idea, as is typical with the western line of thought, is that a true artistic subject can only be the uninfluenced creation of an individual artist. Therefore, an artwork had to be “self-drawn” (jiga), “self-engraved” (jikoku) and “self-printed” (jizuri) in order for it to become a genuine expression of the self. In other words, the artist had to be the one and only maker. The related philosophical debate, revolving around the notion of artwork, was spurred on by a pair of writings entitled “A green sun”, 1910, by Kōtarō Takamura (1883–1956), and “Bunten and the Creative Arts”, 1912, by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916). According, say, to the first reference, if some artists wanted to paint a green sun they should have done so.

The Fisherman by Yamamoto Kanae (1904)

From the Sōsaku-hanga representatives’ point of view, the Shin-hanga was seen as a commercial art, promoted by a businessman like Shōzaburō, to satisfy the tastes of the western market and thus deprived of originality, freedom and personal touch. Watanabe Shōzaburō tried to defend himself against accusations of poor creativity by emphasizing the innovative quality of, and even coining the “Shinsaku-hanga” (new creative prints) term for, the Shin-hanga-related prints.

For the sake of precision, as raised somewhere, the western concept of “creativity” was to some extent misinterpreted or abused. In fact, although western art gives great importance to the individuality of the artist, it was not unusual for artwork ateliers to be commissioned, in which case the investigation on the very contribute of an individual artist could be restricted or difficult to single out. In addition, the Sōsaku-hanga artists were not adequately versed in the sophisticated carving and print techniques, the consequences of which were the rudimentary, naïve, almost unrefined craftsmanship of some prints which, on the other hand, was successfully taken as a distinctive feature in the collectors’ world.

Likewise the Shin-hanga, the Sōsaku-hanga gets rid of the outline usually adopted in the ukiyo-e. The Sōsaku-hanga subjects, however, depart from those typically in line with the Japanese tradition as to variety and eclecticism, because they happened to be a convincing expression of the author’s radical subjectivity. The Shin-hanga is prone to watch Impressionism, while the Sōsaku-hanga is rather subject to the influence of the German Expressionism and abstract art, and is additionally prone to watch the western art’s avant-gard movements.

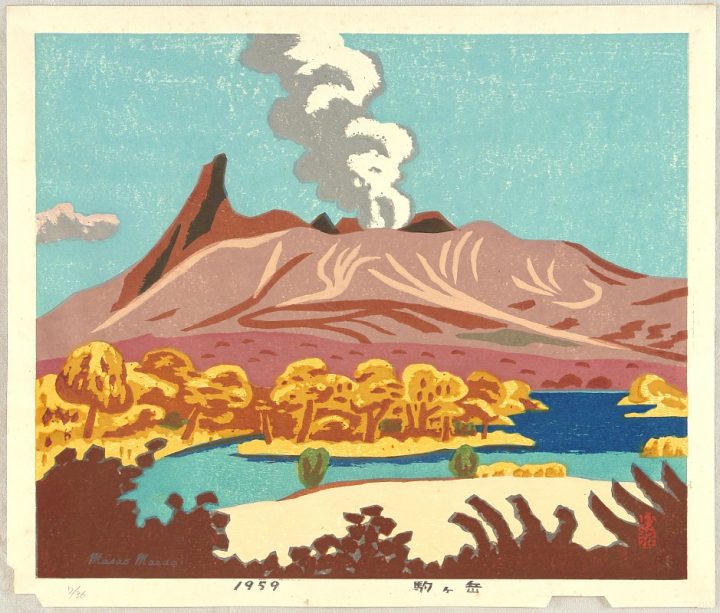

Masao Maeda, Mount Komagatake

Sōsaku-hanga leaders got way of attending high schools for performing art in Paris, Rome, Berlin and hence let those movements affect them. In the late 1800s, hence, in the midst of the westernization cultural policy, the Japanese government moved students to the West within the framework of higher-learning actions in the fields of engineering, law, military science and western art. Further informative and influencing sources on the European art movements were a number of journals, say, the German Jugend and the Japanese Hōsun.

The Sōsaku-hanga was hardly a successful movement when it was starting out because of its own non-profit-making vocation and the concurrent mistrust raised at home. Therefore, the related artists often used to practice ordinary professions owing to the small profits derived from their artistic activity. As an example, Sumio Kawakami (1895-1972) was an English teacher. The movement was later supported by specialized journals and associations whose founders were the members themselves, but managed to internationally succeed only after the World War II. In fact, it was exactly during the American occupation of Japan that a U.S. collector and Japanese-art scholar at once, named Oliver Statler (author inter alia of a 1959 publication entitled Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn) discovered the “creative prints”. It is safe to say that the market of prints did concur to rebuilding the Japanese postwar economy, even though the attention of the U.S. collectors shifted from the Shin-hanga towards the abstract art channeled into the Sōsaku-hanga.

Maki Haku, Work 73-18 (1973)

A returning western interest for the Japanese prints remarkably enlivened after the war because of the so-called Ichimokukai (the First Thursday Society). It was founded since 1939 by an artist team that would gather on a monthly basis in Tokyo at Kōshirō Onchi’s (1891–1955) house. After the war, the U.S. Japanese-art specialists Ernst Hacker, William Hartnett and Oliver Statler also attended those meetings. Also important for the movement success were exhibitions abroad, notably the Sao Paulo Art Biennial that was held in 1951, in the context of which Kiyoshi Saitō (1907–1997) and Tetsuro Komai (1920-1976) did assert themselves. For the sake of completeness, further artists deserving of mention as Sōsaku-hanga leaders are Un’ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997), Sadao Watanabe (1913–1996) and Maki Haku (1924–2000).

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved