The opening to the West from the Meiji eve gave vent to new cultural and artistic pattern models for the Japanese society, without interruption until today. The modernisation process undertaken and the increasing industrialisation were instrumental for the Japanese women to come out for the first time from their own private universe, so they can make their debut with the public life once exclusively reserved for men. The woman worker is also an economically independent consumer, enjoys far greater freedom of movement and independence, such as turning for shops, drinking, smoking, attending the premises, going a cafe. Clothing and hair follow west trends in such a way as to meet the needs of an increasingly fast-moving life.

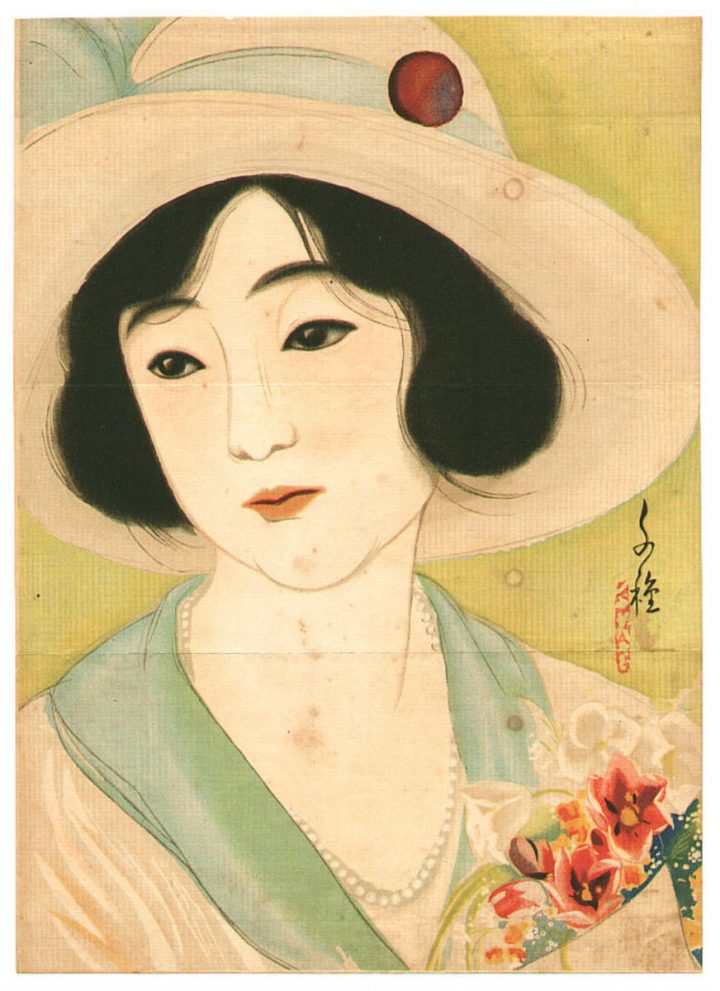

Kitani Chigusa, Lady in Modern Dress in the Taishō Era, between 1912 and 1926

The woman representation in line with the shinhanga, hence, during the Taishō and Shōwa periods, is a meaningful indicator of a complex and inherently contradictory transitional phase of Japan from tradition to modernity. In fact, that phase mirrors the tension of the cultural world between the opposite poles of opening to new ideas from the West and nostalgia for the past, the latter being romantically idealised by Western collectors and still contemplated in terms of identity bulwark by the Japanese. In this respect, the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō played a key intermediation role between typically Japanese and Western iconographic, technical and stylistic elements. That editor radically renovated the face of the bijinga classified ukiyoe, by a process of purification from any form of “vulgarity”. The aim of this activity, consisting in a skilful balance between modernity and tradition, was to gain, on one hand, the contemporary audience, always curious about and keen on something new from the West, and not shocking, on the other, the most traditional-minded margins of society, nor infringing the censorship.

Kitani Chigusa, Beauty and Cherry Blossoms

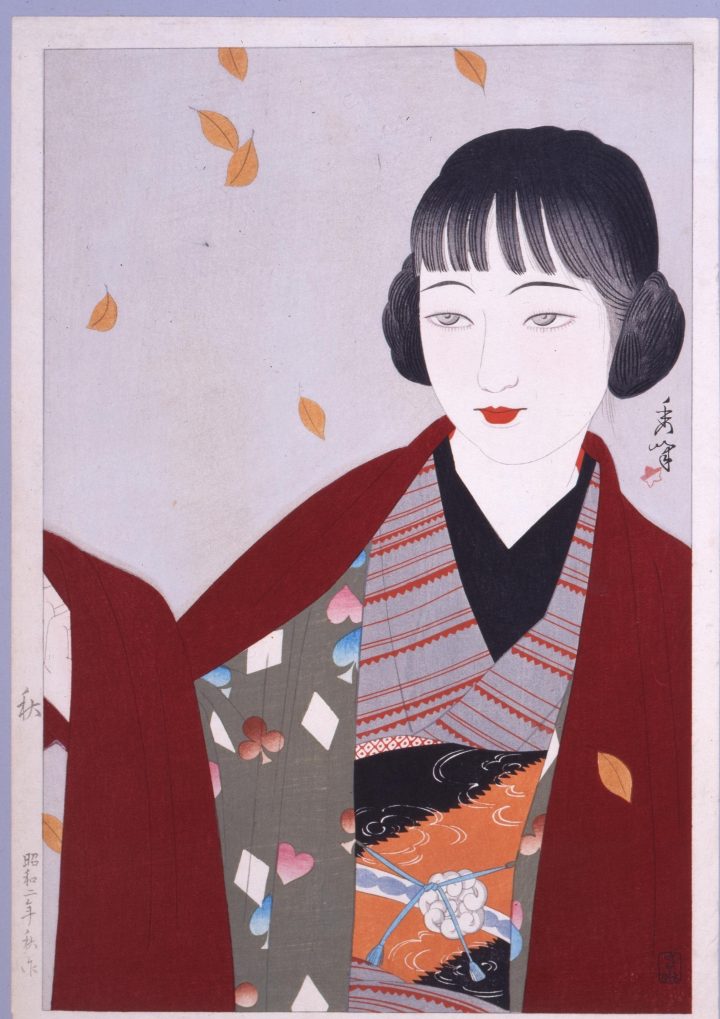

As an example of the above solution “in the middle” could be the geisha imaging that turned from the explicitly erotic icon, typical of ukiyoe, of an ambiguous and transgressive world, into one that rather evokes with reassuring tranquillity the Japanese traditional values. In fact, the geisha currently embodies a sweet and modest, as well as nostalgic and dreamy, femininity like if she had longing for herself. The undercurrent of sensuality is attenuated in the portraited geisha by the fact that her presence actually evokes themes and situations according to the most authentic tradition, such as religious festivals and seasons. In particular, the image of woman-season link, in conjunction with the nature symbolism as a metaphor of the purest, even though fleeting and ephemeral, feminine beauty, had the function of leading back the woman representation to the canons of the most authentic artistic literary tradition of Japan.

Yamakawa Shūhō, The Autumn, from the Series Four Women, 1927

Against this soothing background, the innovative quality of prints at hand stems from the overall appearance of the human figure, which looks like it is less stylised, more highly naturalistic in relation to features and posture, with a hint of plastic volume. This is rendered by using well-though-out colour effects that, however, are not detrimental for the classically chiaroscuro-independent, linear and two-dimensional setting. The outline itself is no longer sharp, thick, black as it is the case for the ukiyoe; conversely, the contours are drawn slightly, bleached, sometimes highlighted with an unprecedented relief engraving technique. Last, an innovative iconography is developed by introducing little details, such as hairstyles according to the Western fashion, an unusually patterned kimono. Perhaps, the most striking rendition is furnished through the shinhanga print of a geisha who smokes on a break, although the departure of that subject from tradition is attenuated by a typically Japanese firework that is visible outside the window. However, some typical ukiyoe prints do capture, do not forget, geisha and courtesans smoking a pipe or drinking sake. Parenthetically, in my opinion, the novelty of those printing, and the risk of censorship they runned, was due to the fact that they rather presented as translations in a “Western” language – made of cigarette and cocktail tacitly evoking a generally transgressive style of life that has fatally contaminated the society as a whole – than as a means to make visible, as such, the nature of those unavoidable pleasures.

Ishii Hakutei, Yanagibashi, from the Series Twelve Views of Tōkyō, 1910

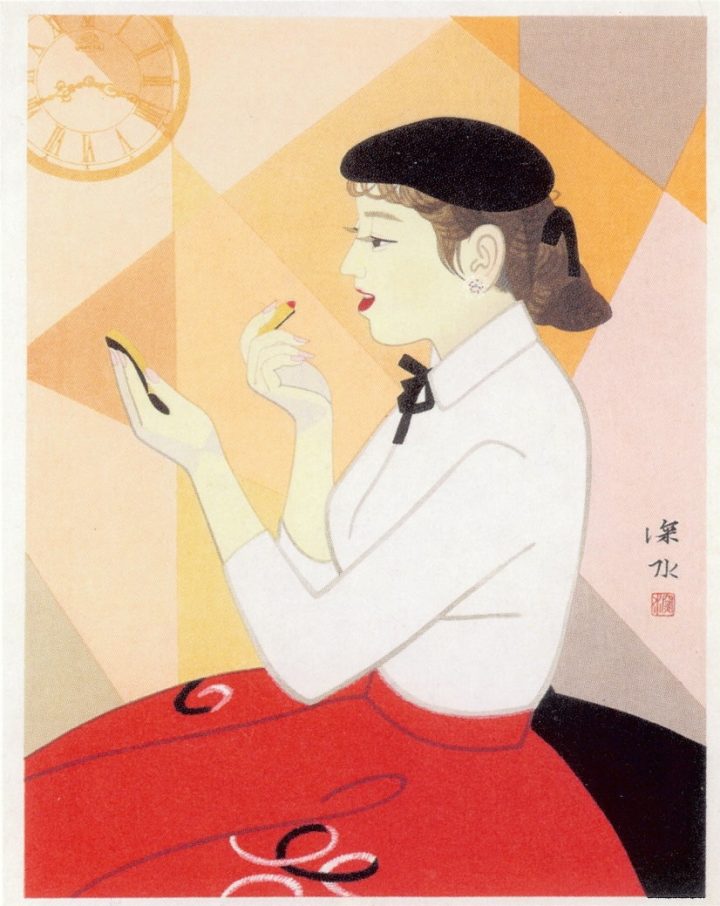

A direct competitor to the geisha, the latter rather seen as a revised epitome of the Japanese history and tradition, is the moga who manifests a clearer and definitive break with the past. Moga means modern garu, in turn a Japanisation from the English modern girl. Clearly, this is a case of neologism, first adopted in the report of a Japanese newspaper designed for women readers. The subject regarded a new typology of woman, one prone to challenge conventions and break rules in relation to the still existing social behaviour, apparel and life choices in Japan. In other words, it comes delineated the picture of a free and “anarchist” woman, a true protagonist of the society, hence, able to play an unhinibited role even in the relationships with the opposite sex. The moga is defiantly captured in the shinhanga prints with bobbed or curled short hair coming into fashion in the 1920s; she is artfully adorned with watch and jewelry to function as a symbol for the achieved equal economic independence; she uses to wear Western clothing which leaves the shoulders, arms and legs discovered, and is inclined to assume the attitude of those who are smoking, drinking cocktails or dancing in a typical dance hall.

Itō Shinsui, Clock and Beauty (IV), 1964

Last, the woman is conceived in the bijinga ukiyoe – likewise in the shinhanga prints representing traditional beauties – as a mere object of desire: her glance is never direct; instead, she is often recorded in the act of wearing make-up, combing her hair, get out of the bath, so as to create a suitable voyeuristic atmosphere for a discreet observer. In the moga, instead, the feminine subject has at long last her eyes directly turned towards the spectator, thus triggering an erotic interplay on the edge of the provocation and reaction.

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi, Tipsy, 1930

Often, bar, cafe and dance hall were ambiguous venues where prostitution was taking place; in fact, the moga was ofted regarded as a new courtesan, although dressed in the Western manner. Her appearance, far from being a convincing expression of women’s liberation, was harshly criticized in feminist key as a new way of reduction of the woman to sexual object.

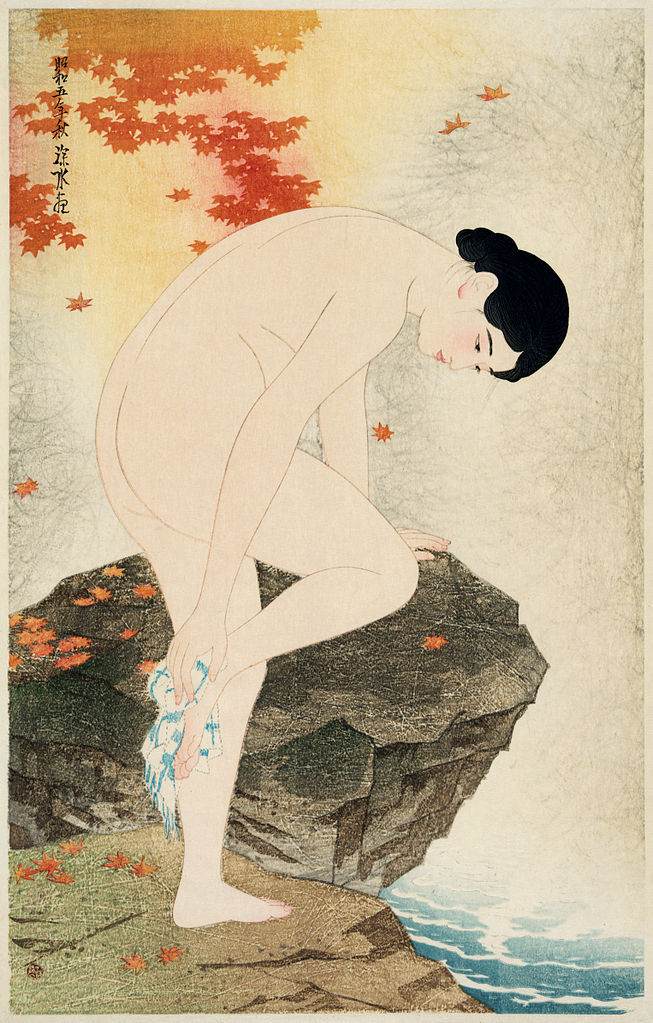

A special consideration should be done for the theme of the female nude. It has already been said as regards the feminine nude that it was almost never explicitly represented in the bijinga. Even in the shunga, i.e. erotic prints, lovers are always partially dressed. Only exceptions are scenes where women are getting out of the bath, or engaged in another activity always related to bodycare. In them, however, partial nudity is functional in nature, as it is linked to the performance of these activities. A further exemption is the representation of feminine figures in the composite realm of myth, tradition and folklore, where a remarkable place is occupied by the ama, as the pearl fisherwomen are specifically termed.

The openness to the Western art allowed the Japanese artists to know for the first time the artistic nudity, understood as study of the human body with a not necessarily erotic meaning. The pioneers who approached the depiction of nudes were the Yōga painters (members of the current that established a rupture with the Nihonga in order to open up to West derived oil painting): they were allowed to represent nudity because of the restricted audience of this class of paintings if compared to that of prints. Instead, the nude cannot slip the censor’s net in relation to the shinhanga since the prints had mass circulation. With a view to circumvent that prohibition, the shinhanga authors adopted the stratagem to represent nudity, in whole or in part, in a context which could justify it, namely the one linked to personal care activities and, in particular, to the bath. The latter, in fact, becomes meaningful in terms of a ritual ablution, thus inherently respectful of the purity-cleanup principle implemented in the Shintō religion. On this basis, the bath under examination fits into the traditional scenario reminiscent of the ancient moral values proper to the Japanese society, thus counteracting the Western-style innovative representation of the disrobed body. With these premises, the nudity is rather discreet and the woman is pudish in her attitudes: she is often captured while crouching with a towel around her waists and languidly absent look. An innovative technique involving the baren makes the idea of vapor into the air of the bathroom, so that the atmosphere is rendered in a more faded and soft fashion.

Itō Shinsui, The Fragrance of a Bath, 1930

The series entitled “Ten Types of Female Nudes” by Ishikawa Toraji, completed in the year 1935, did break the previous conventions and, then, was heavily sanctioned by the current system of censorship. In that series, the nude subjects do not display the typically Japanese features, nor the iki rules. The representation follows the Western style, thus characterized by large-dimensioned masses for the body rendering. The nude is performed deliberately, without any discernible reason – with a few exceptions as those regarding the bath – and clearly displays sensuality, often marked by the fact that the subject is steadily looking at the spectator. But far from being contextualised in the Japanese tradition, the unconventional approach at hand is highlighted with the spirit of the West, this being easily recognizable by the description of imaginative, brightly colored patterns after Matisse, suitably furnitured and decorated indoor scenes, Liberty inspired objects and textures. Women are often portrayed in lazy attitudes, such as leafing through a magazine or playing with a pet, considered contrary to the morals of commitment and sacrifice advocated by the government of the time: for the first time a “modern” and shopenhauerian state of mind like boredom is depicted.

Ishikawa Toraji, Bored, from the Series Ten Types of Female Nudes, 1935

Cover image: Okamoto Toko, Let Out, 2014

References: https://ds-omeka.haverford.edu/japanesemodernism/exhibits/show/the-female-image-in-shin-hanga

http://dspace.unive.it/bitstream/handle/10579/11477/836207-1202912.pdf?sequence=2

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved