The cherry tree (sakura) is one of the primary concerns of the Japanese culture, also for the historical reasons that will be exposed as follows.

Plum blossom blooming in winter, when the earth is still covered with snow, is the one that once was taken in Japan as a springtime symbol, because it was evocative of the courage to resist bad weather while retaining delicacy and frailty. Therefore, that pivotal symbol was associated to the Nara eve (710-794), just about the time that cultural influence of the Chinese Tang dynasty was strongly perceived. Things changed in the Heian eve (794-1185), namely when relations with China broke off and the cultural attention was thus paid to all that was originally Japanese.

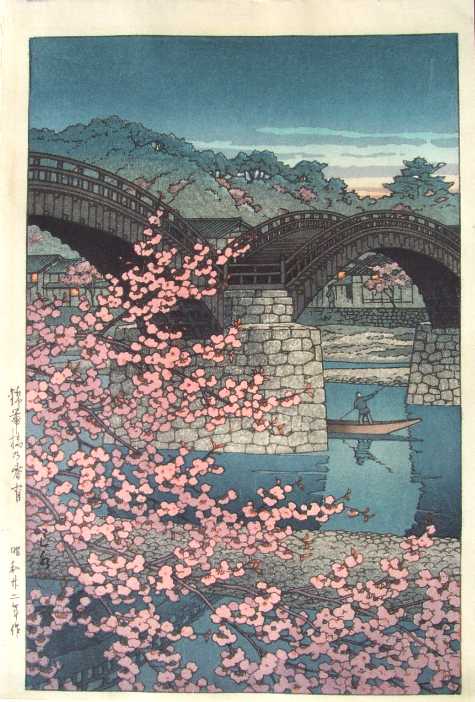

Kawase Hasui, Spring Evening at Kintaikyo Bridge, 1947

Against this backdrop, it was precisely the cherry tree which became the epitome of the springtime awakening of life in the nature. This because the above-mentioned tree was felt as being intimately connected to ancient agricultural rites, notably, those pertaining to the cultivation of rice – a cereal species of primary importance for feeding in Japan – whose sowing is done exactly in the period of cherry tree flowering. In fact, the villagers believed that the mountain divinities turned into the rice kami, a metamorphosis that could only take place when the petals of the cherry blossom dropped on the mountains, where the cherry trees once stood. It was also the custom to predict the state of harvest of the rice by observing the cherry tree’s appearance and flowering. In addition, the fertility of that harvest was propitiated with food and sake, which were placed under those trees. The word sakura itself derives, according to some, from the term kura which indicates the warehouses where rice is stored. Others instead highlight the root saku connected to the verb to flourish.

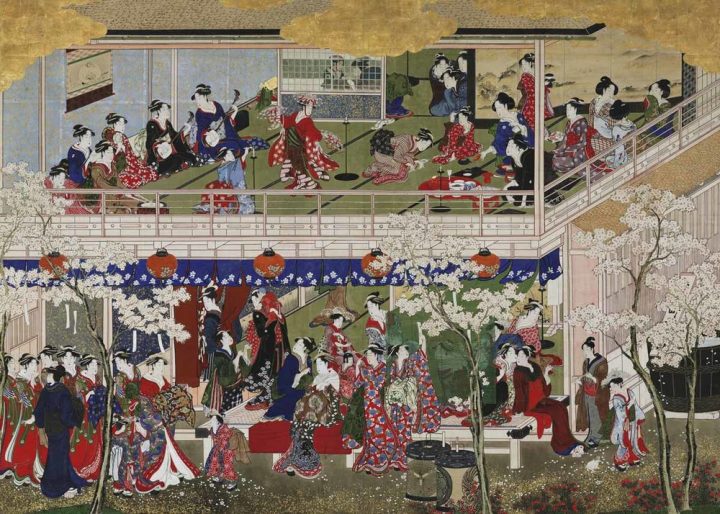

Kitagawa Utamaro, Hanami, 1793

In spite of the rural origin of the veneration for the cherry trees, the use of enjoying views of the blooms while writing poems, playing music and drinking sake, was typical of aristocratic ambiences as it was the case for the imperial court during the Heian period, namely when art was one with life. The first hanami was established by the Emperor Saga (786–842) after eradicating a plum tree from the garden of the Imperial Palace and replacing it with a cherry tree. The term hanami itself is for “looking at (mi) the flowers (hana)” and was first reported in the Genji Monogatari authored by the lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu (XI century). From the Heian eve on, the word hana, previously adopted in poetry to specifically refer to a plum blossom (see, for example, the Man’yōshū, second half of the eight century), was moved just to mean cherry blossom, thus becoming the flower par excellence.

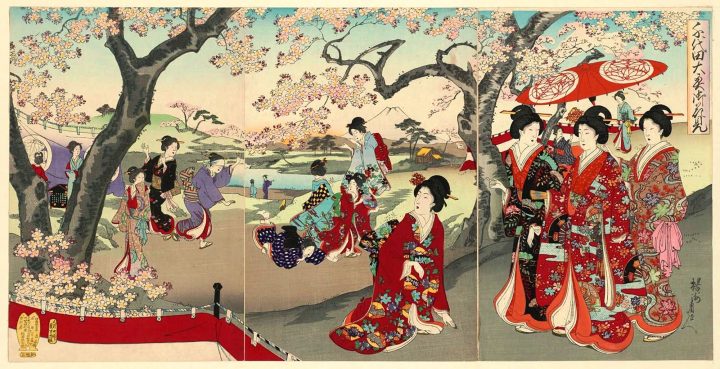

Yōshū (Hashimoto) Chikanobu, Cherry-blossom Viewing, from the Series Chiyoda Inner Palace, 1894

The use of contemplating cherry blossoms in springtime had spread later especially through the samurai who, because of being exposed to the peril of losing their lives, adopted that short-lived bloom as a symbol of an uncertain and transitory existence. The samurai thought that the pink colour of that flowering was evocative of the blood shed in combat by themselves. Finally, the cherry epitomized the virtues that the samurai had to cultivate, that is, simplicity, purity, delicacy with the weak and a willingness to let oneself go at the right moment, that is, to die with courage and dignity (bushidō).

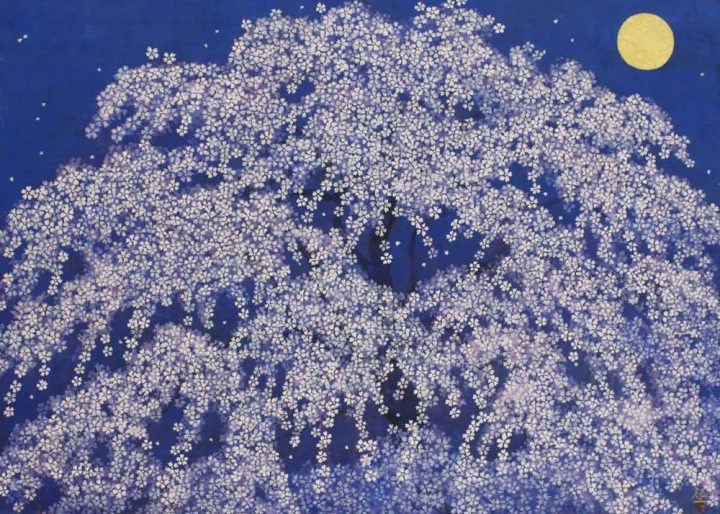

Reiji Hiramatsu, Prayer of Japan, Cherry Blossoms, 2012, Yugawara Art Museum

It was in the Edo period (1615-1868), during which art and life had to be democratised, that the hanami crystallised in the meaning we ascribe to it now, namely as a public, collective ritual of enjoying the sakura between food, music and dance. This also by courtesy of the shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751), who planted cherry blossom trees in Edo, thus creating splashes of pink colour against the grey background of the city, a spectacular visual contrast which is still admired today by locals and crouds of visitors.

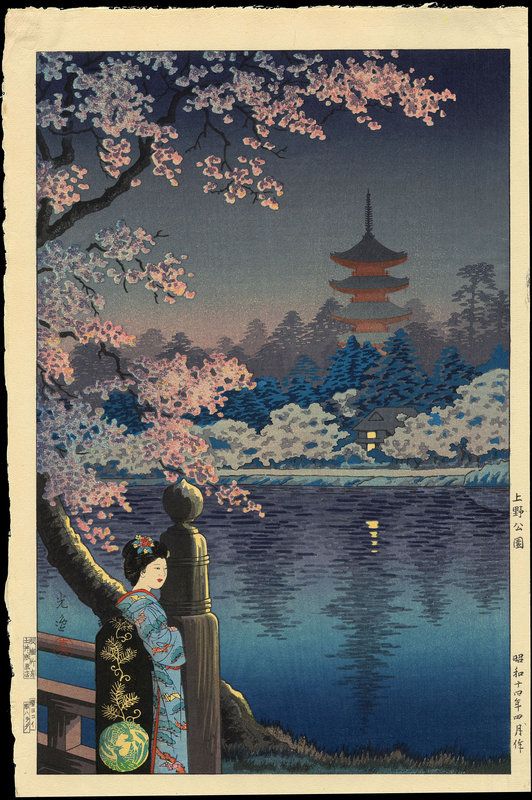

Tsuchiya Kōitsu, Ueno Park, 1939

Parenthetically, the religious significance of the cherry blossom tree cannot be disregarded. The five petals of the bloom under examination represent both the “five orientations” (north, south, east, west, centre) and the “five elements of nature” (earth, water, air, fire, vacuum) according to the esoteric Buddhism.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved