The key position of the human being in the ukiyo-e, especially with regard to the female subject, is to be regarded as an unprecedented advancement of the Japanese art. In fact, preferential attention was previously paid to plants, animals and landscapes, as it was the case under the Yamato-e and the traditional Rinpa and Kanō schools. According to the Japanese sensitivity, love for beauty and sense of poetry, in so far as they are inextricably linked to the mono-no-aware idea – namely to the yearning for all that is transient and brief such as beauty -, both pass from paying attention to the gentleness of flowers or freshness of a landscape in springtime to focusing the feminine charm and poetry. Contemplating a woman is an exercise of ecstatic admiration not unlike the one with respect to the moon and cherry blossoms. As it was the case for the nature representation, where a subtle sense of melancholy merged with exaltation of beauty – the latter increased by being the impermanent result of a season, some days or an instant only -, the invariably emotional contemplation of the feminine figure tacitly understand that youth and beauty are of transient nature. Accordingly, the notion of beauty underlying bijinga (pretty women’s portraits), which is a genre representative of the ukiyo-e, becomes almost “sacred”, even though the portrayed subjects are customarily red-light district women.

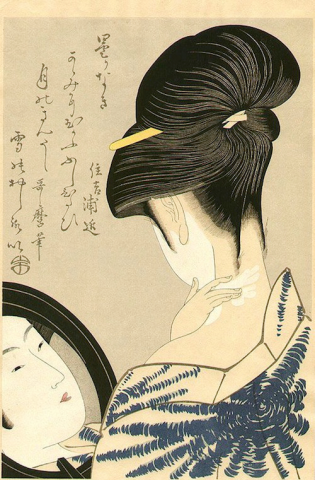

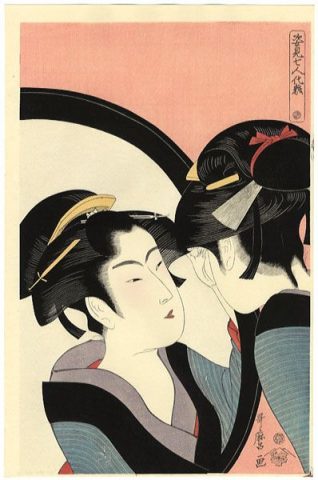

Each culture links the definition of beauty to time-varying aestetic guidelines. These involve fair skin, indeed, skin white as snow, with reference to some literary texts. Such a special canon dates from the Heian period (794-1185) and stems from the aristocratic concept of feminine beauty shielded against sunrays. The camouflage adopted to display a rather white-pinkish provided a mask-like aspect to the female face, as if the art of seduction rather consisted in hiding, rather than revealing, the facial features. In other words, preference was rather expressed for a markedly sophisticated than natural beauty, namely for an artfully manipulated than authentically natural effect. Furthermore, the very act of wearing makeup was taken alluring, so that contrary to Ovidius’ stance which suggests to the women not to show their makeups in the authored Ars amatoria, the most appealing moments captured in the ukiyo-e scenes are precisely those in which women carefully wear makeup.

Eyebrows, thoroughly removed by the married ladies but methodically present in the ukiyo-e as an epitome of youth, are subject to changing trends: according to the influence of some Chinese canons, the original preference for thick eyebrows turned into thin and arched “willow-leaf”-like ones. An upwardly lengthening and narrow eye outline, corroborated by a habit of looking down instead of straight ahead, were guidelines recommended for the feminine beauty. The look is not directed in the ukiyo-e, so that the woman’s charm seems loaded with elusive mystery. Straight nose and small mouth are preferred features; the latter has to evoke, with the help of the colour, a “cherry” or a “fall maple leaf”. This is the reason why the women never put on makeup on the lips completely. They also used to black out the teeth with the effect, also recorded in the prints, of contrasting sharply with the mouth color.

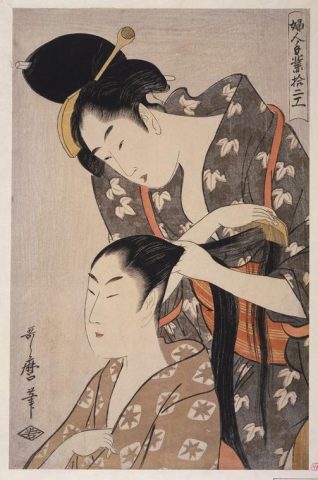

The original preference for rounded faces and bodies, so as to manifest a state of prosperity, turns into thinner shapes in conformity with both the Chinese elegance canons, according to which the woman should appear supple “like a willow”, and the aesthetic iki ideal. An elongated and slender appearance involves arms, hands and, even, fingernails. It is no accident that the grace and finesse of the hands are successfully rendered in the ukiyo-e, notably in the act of arranging hairstyle, playing an instrument, or opening a letter.

Shifting attention from the aesthetic canons to the feminine representation, in work of art, provides an opportunity for realizing that nudity rather falls outside the ukiyo-e representation. An explanation for this trend could be the concept of courteous beauty, inherited from the Henian period, that rather saw in the dress an instrument of seduction and interpreted beauty in the overall sense of refined and elegant allure. Geisha and courtesans were in fact icons of style, dressed in an oversophisticated, expensive and fashionable way.

In addition, the ukiyo-e prefers a just touched nudity than an immodest counterpart: the most sensual zone of the feminine body is the back of the head, which is the only one left exposed by the kimono edge. Even the sight of a bare foot or part of the leg resulted in an immensely seductive experience owing to the contrast with the covered rest of the body. Therefore, the geisha worn sandals without stockings even in winter. Very attractive was figuring out the petticoat under the pieces of the kimono or guessing how a specific woman could seem just out of the bath.

The ukiyo-e artists are prone to capture intimate and solitary moments of the women, namely when they wear makeup, comb their hair, read love letters, with the ultimate intent to express at their best some characteristic gestures or spontaneous reactions.

And deep down, the involved artists were trying to grasp the mystery of womanliness, the female soul that reveals herself, for those gleaned moments, as the innermost layer of the kimono.

Copyright © arteingiappone – All rights reserved